So, grad school is a lot of writing, and the past year has seen a lot of change in my life. The result? No Substack posts. The good news? I’m posting now. The bad news? This is a review essay I was generated for a class which I feel like fits with the general theme of my newsletter – so now you get to read it too, if you want. Looks like this now is a Chicago Manual of Style publication! Anyways, enjoy some theory, why don’t you?

Also: massive spoliers for the incredible Disco Elysium ahead. You should play it if you haven’t already. It came out in 2019 so it’s fair game.

“0.000% of Communism has been built. Evil child-murdering billionaires still rule the world with a shit-eating grin. All he has managed to do is make himself sad. He is starting to suspect Kras Mazov fucked him over personally with his socio-economic theory. It has, however, made him into a very, very smart boy with something like a university degree in Truth. Instead of building Communism, he now builds a precise model of this grotesque, duplicitous world.” (the solution to the “Mazovian Socio-Economics” thought in Disco Elysium)

“Apropos homosexuality, Oscar Wilde cited ‘the love that dare not speak its name’ – what we need today is a Left that dares to speak its name, not a Left that shamefully covers up its core with some cultural fig leaf. And this name is communism.” (Žižek 2020, 6)

Beginning to Get Organized

When prompted in Disco Elysium with the task to “get yourself organized,” as a player I am confronted, as with so many other quests in the game, with an ultimately futile endeavor. “Building communism” in the district of Martinaise, a constituent part of Revachol – a city on an island off the fictional Insulindian peninsula – is not an achievable goal. A formerly communist enclave crushed by the Coalition of Nations, an international alliance of capitalist states, in a brutal war decades before the game properly begins, Martinaise is a primary site of poverty and exploitation within the city: a slum populated by underpaid dockworkers, shipping being the area’s primary industry; impoverished fishing folk; and social outcasts unable to live elsewhere. The avatar of an amnesiac, alcoholic detective serves as my vantage into this distinctly everyday tumult, unreliable and unstable, he not only needs to “get [himself] organized” in the sense of his burgeoning left-wing radical “Mazovian” socioeconomic analytic framework, but also in the very real everyday which he inhabits. This self-organization, too, is a Sisyphean errand: as the game progresses, its world becomes less organizable – and our detective, less able to organize himself positively in relation to it. In a sense, the futility of him “building communism for all” is reflected in the futility of meaningful self-organization in a system, indeed a world, which itself is spinning increasingly towards escape velocity from anything perceptibly rational. Disco Elysium is just the most notable in a left-wing movement in videogames which play with these themes of futility, and which are reflective, and products, of the contemporary place in the global sociopolitical paradigm – one itself of alienation, depersonalization, and futility in the face of systemic exploitation.

Disco Elysium itself is a non-combat point-and-click narrative role-playing game, in which the detective in question wakes up from his bender the night before the game begins properly and finds himself clueless in the middle of a murder investigation. The Insulindian peninsula itself is part of the ‘New World’ of the titular planet ‘Elysium,’ which colonists came to and imposed foreign, oppressive systems upon for the purpose of resource extraction. It is now governed by the centrist ideology of the Moralist International, or ‘Moralintern,’ which is functionally the International Monetary Fund, with the backing of the aforementioned Coalition of Nations, functioning as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. These two groups have worked together to impose a neoliberal “transition government” upon Revachol and maintain its status quo since their invasion and the destruction of the communist revolutionary government. Known as a member of the Revachol Citizens Militia, the region’s police force, the detective who initially remembers nothing prior to the alcoholic stupor with which the game begins, re-learns about this world from the citizens of Martinaise, who mostly either distrust and despise him: an arm of the regime which would see them continue to suffer.

Two strikes

While I have had a copy of Disco Elysium in my possession for almost a year, and have planned to play it since its release, I was spurred to finally engage with it again by the University of California academic workers’ strike. Prior to the strike, I had played Backbone, a tonally similar left wing neo-noir which explored a life after humanity had evolved, and had destroyed the planet outside of cities à la Dick’s perennial classic Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? or Hideo Kojima’s walking simulator Death Stranding. Ending with the player character walking out into the sea of dunes surrounding the city and collapsing after becoming the subject of a corporation’s laboratory experiment – following an investigation-gone-wrong of cannibalism of working class citizens by their executives – on the false hope that life would be possible outside the walls, Backbone shares with Disco Eylsium a feeling of crazed, individual helplessness in a system, and a narrative, which is built to break the player down. This feeling resonated with me during the strike in the real world: the overwhelming sense that, no matter how organized, the systems which are, the powers that be, are unshakably rooted in our world and in our lives. Not only did the strike feel like it was pushing against a cultural object which was sublated into the everyday functioning of life, but that the strike itself had come by its second week to the same fate. The hastening of normalizing processes through hyperconnectivity by a sort of collective intelligence (Lévy 1997, 13-15) – distributed, mediated bystander communities finding answers and solutions for the crisis of contradiction without addressing it. A depressive hedonia which manifests in dull, reactionary discontent among those affected by the struck labor, seeping even into those striking because it is not pleasurable or perceptibly under Control (Fisher 2009, 21-22).

In Disco Elysium, too, a strike is a main point of contention for our player character and the district of Martinaise. On strike to make “every worker a member of the board,” the dockworkers of the Greater Revachol Industrial Harbor understand that their position is not one which can be met realistically by their bosses. Nevertheless the workers control access to their workplace, and can seemingly strike indefinitely with the support of their union – despite armed counter-organizer mercenaries who eventually kill members of the union in a climactic shootout. The literal idealism of the demand, to essentially turn the docks that the workers are employed at into a cooperative, is balanced by a sharp literary cynicism, characters engage with their own strike with a dual sensibility: first, of loyalty to their coworkers and the cause; and, second, a tongue-in-cheek knowledge that their goals are never going to be met.

At once Disco Elysium betrays the importance and struggle of unionism as a practical implement of change. The unshakeable solidarity of unionized workers with each other operates throughout the primary storyline of the game, protecting its members from the police as they investigate the murder of a strikebreaking private mercenary, as well as providing for their basic needs in the face of the wear of the strike. Despite its fundamental corruption, with a cartoonishly large union boss as its leader and various elements of nefarious business ranging in extremity through serial murder, the union clearly is driven with the goal of improving its members’ lives in mind. As an organization though, it exists in a constant state of suspicion – insular and untrusting of anyone from beyond its ranks. Torn between their own misdeeds and the violence of capital being inflicted upon them on both a structural level, by the Coalition, and on an individual level, by hired mercenaries, union members have reason to be suspicious. This self-insulation is also physically represented in the geography of the game’s map, with a primary objective for the first third of the game being to even get beyond the massive gates which wall off the harbor from the rest of the city, closed off, and enforced as such, by striking workers. This closure effects the entirety of the Martinaise everyday, with long-haul trucks backed up at the entrance of the harbor creating a physical obstacle for traversing the space of play. Despite being a sort of extension of the strike itself, the physical disruption undergoes a sort of Hegelian sublation in which it becomes a normative part of the structure of the city, but also is ignored as such (Erdmann 1896, 29-30). The negation of its normalcy, itself becomes normal, thus ensuring its continued presence.

Indeed, the interconnection of the very real political economy of labor activism and ontological suspicion is something Disco Elysium portrays with finesse. In my own experience, the repressive apparatuses which spur strikes and other demonstrations do not just undermine them through the direct pushback inherent in such confrontations, but also through undermining the basic structure of top down organization. In What is to be Done? Lenin lays bare the way that these sorts of issues holds back labor organizing as a whole in the struggle for “building communism” in that they cannot be politically radicalizing on their own. The structure of unionism, in which bureaucracy is mediating forces at play both internal and external, opens it to a bifurcation of the “economic” and “political” which degrades the power of movements, and disassociates the ideas behind an action from its praxis and “plays into the hands of both ‘Economist’ and liberal opportunism” (Lenin 1961, 37-38). This full disassociation of praxis, ideology, and the political economy of action felt all the more relevant in the internal counter-organizing which plagued the UC strike, in which a minoritarian viewpoint believed that the extension of a partial strike or that the simple withholding of labor would be sufficient to pressure the state into further concessions in contract negotiations – and that the ideological underpinnings of the strike, as well as demonstration itself, was irrelevant to reaching the end goals. Their striking was that of pure ideology, a “’hollow sound’” which did “’not promise palpable results’” (Lenin 1961, 38).

This sort of demonstration, is perhaps similar on its face to that of the dockworkers’ in Disco Elysium, but in its relationship to a wider situation is different – with nothing to lose in the full destitution of their living situations and full solidarity the strikers of Martinaise can afford a strike of pure ideology. The chant “who protects us, we protect us” comes to mind. In reality, such an action is untenable without those fully dis-/utopian conditions, respectively. The more interesting point though, is that both in Disco Elysium’s harbor, and at the UC campuses, the strikes are exercise in futility. The power of labor without political education is incapable of reshaping society at its core, they all work within the superstructure built upon the base of the late-capitalist state, in which private economy has synthesized with government – and public goods have taken the shape of private enterprise (Althusser 1970).

This futility is felt throughout Disco Elysium’s world. The entire map is caught in stasis: the snow on the ground never melts; the trucks are stopped at the dock gate, debris all around them, goods half-unloaded; the ghostly echoes of answering machine messages past paranormally linger in their speakers; even the statue of Revachol’s former suzerain is preserved in the state of its destruction at the hands of the communist revolutionaries, for artistic purposes. This may seem in contradiction with the idea that the world is simultaneously spinning ever more out of rational control, but the continued unchanging nature of Martinaise’s structures of feeling (Williams 1977), despite its many would-be disruptions and internal contradictions, itself is the irrational and surprising uncontrolledness of the world. Both as a player in the game, and as a striker-organizer, I have no control over the repressive apparatuses which govern my existence. The inability to change the core structures of society and governance, and ultimately everyday life, through any organization is the fundamental futility of organization under late-capitalism which Disco Elysium so well portrays.

Book club praxis

The thin stand-ins for Marx and Marxism in Disco Elysium are “Kras Mazov” and his theory of “Mazovian socio-economics,” the core tenets of ‘real-life’ Marxism remain intact in these Elysian versions with some new additions and variants based on the historical context of Disco Elysium’s world. Of course, along with Marxism come the reading groups. As a former member of a Marxist reading group, and a prospective member of another, I all too well understand the culture of these things – they are unabashedly overwrought and performative. Nevertheless, I am magnetically attracted to them. They are loci of political education which, however an individual may choose to engage with, can generate new ideas about society and help to reinterpret the old. They can generate strategies for “building communism.” They can do all these things, yet so often they do not.

Disco Elysium knows the track record of reading groups all too well. In the quest to build communism in Martinaise one might stumble upon, and ingratiate themselves to the local Mazovian socio-economic “infra-materialist” reading group. A play on the very real theory of historical materialism, as well as seemingly lightly inspired by the new age apocalypse Trotskyist cult of J Posadas (see: Gittlitz 2020), infra-materialism is an idea borne from the supernatural reality of the game’s world. When first encountered, the two-member student communist group is attempting to build an impossible structure out of matchboxes, but when the detective arrives it falls down. After questioning, they decide that he does not yet believe in or understand, to their standards, communism. They then go on to assign the player reading, which lays out their theory of communist thought – not just socio-economically, but materially in the dictionary sense. Adherents to the in-game Mazovian “philosopher” Ingus Nilsen, they gift a copy of his book: A Brief Look at Infra-Materialism. There will be a quiz on this later. Infra-Materialism, according to Nilsen, is the idea that thoughts are not simply contained within the mind, but radiate out from it in “rays of politicized energy” or “plasm.” This plasm, these thoughts, have the ability to effect the world around them, to effect material reality. The inspiration of revolutionary plasm, Nilsen and the infra-materialists surmise, could improve crop yields, allow for telepathy, and even allow for a whole new form of communist architecture accounting for the plasm’s ability to hold structural weight. The two remaining members of the reading group itself expelled its last member for implicitly denying the reality of “plasm,” or at least its effect, stating that “Turnips don’t care if they are grown by communists, moralists, or welkin [communists, liberals, or fascists]. They grow just the same.”

While politicized rays of communist energy “plasm” are not themselves real, the idea does operate, in some respects, like facets of real organization. Infra-materialism calls to attention the shortcomings of “utopian socialism” and its inability to explain social forces when compared to its counterpart, which was supported by the in-game dismantled revolution, of “scientific socialism”:

“active social forces work exactly like natural forces; blindly, forcibly, destructively, so long as we do not understand and reckon with them. But once we understand them, when we grasp their action, their direction, their effects, it depends only upon ourselves to subject them more and more to our own will, and by means of them to reach our own ends.” (Engels 1972, 68)

The discarding of nominally ironic, material realities, in favor of a paranormal faith in the cause, in the power of pure ideology. Thinking is being, and with enough belief, through collective plasmic power, the world spirit would simply manifest communism into being. Historical materialism’s dialectics would be solved. The arc of moral justice would meet its final point. Today in-the-world, and in Disco Elysium too as the solution to the “get yourself organized task” shows, these vulgar notions of fate are no longer sufficient. It is simply Lacanian jouissance: “ideology serves only its own purpose, that it does not serve anything” (Žižek 2008, 92). Žižek’s read of Lacanian jouissance here describes well the non-knowledge of infra-materialism itself: approaching knowledge means diminishing enjoyment. Understanding the world’s material reality means enjoying it less, an irreversible loss of enjoyable ignorance (73).

This is not to say that ideology has no place in society. After all this essay is itself a sort of exemplar in book club praxis: the regurgitation of reflective analysis based on theoretical interpretation – this irony is not lost. It is simply to demonstrate another exercise in futility. Žižek himself recognizes this contradiction, although perhaps more optimistically framed, in more recent writing:

“The old 1968 motto, ‘Soyons réalistes, demandons l'impossible!’ remains fully relevant - on condition that we take note of the shift to which it has to be submitted. First, there is ‘demanding the impossible’ […] This provocation has to be followed by a key step further: not demanding the impossible from the system, but demanding the "impossible" changes of the system itself. Although such changes appear "impossible" (unthinkable within the coordinates of the system), they are clearly required by our ecological and social predicament, offering the only realist solution.” (2020, 146)

This unthinkability was previously explored by British cultural critic Mark Fisher, who described such a psychological condition as “capitalist realism” in the eponymous manifesto:

“Capitalist realism is therefore not a particular type of realism; it is more like realism itself. […] The ‘realism’ here is analogous to the deflationary perspective of a depressive who believes that any positive state, any hope, is a dangerous illusion.” (2009, 10-11)

I myself, and I think Disco Elysium too, are amenable to this view – that capitalism is a Deleuzian “dark potentiality which haunted all previous social systems” (Fisher 2009, 11). Althusser describes ideology as a tool which societies use to cohere, as a “structure essential to the historical life,” and that it is the way in which people come to understand their place in the world (1964). Material history, for Althusser, becomes ideology; and this too can be true of liberalism, for Marxism is not the only contestant vying for hegemony. This is the use of ideology though, despite its frequent use to abdicate the responsibility to take action, when understood en masse it has the power to, again ironically, unconsciously guide society’s collective consciousness.

A friend of mine who completed a playthrough at a similar time to myself said that an interaction towards the end of the game brought him to tears with its depiction of this view: in a near-final section, the detective meets a previously unseen species of insect capable of telepathic communication. In “speaking” with him, it expresses an understanding of this potentiality which radiates out from humanity:

“The moral of our encounter is: I am a relatively median lifeform – while it is you who are total, extreme madness. A volatile simian nervous system, ominously new to the planet. The pale, too, came with you. No one remembers it before you. The cnidarians do not, the radially symmetrics do not. There is an almost unanimous agreement between the birds and the plants that you are going to destroy us all. […] You are a violent and impossible miracle. The vacuum of cosmos and the stars are burning in it and you. Given enough time you would wipe us all out and replace us with nothing – just by accident.”(Insulindian Phasmid, Disco Elysium)

The “pale” is a sort of dark matter-like “human pollution” which exists in both psychic and physical form, connecting one place to the next and covering 72% of Disco Elysium’s world and is expanding at an unknown rate, in the game’s lore. In the game it is described as being composed of suspending “physical, epistemological, [and] linguistic” properties, researchers believe it to be the physical manifestation of decaying thoughts. It itself may be the other side of infra-materialism’s plasm, the destructive force of expanding ideological waste. In reality it may represent the future, as the Phasmid says: the ever spreading foreclosure of both past and future place, reality, and communication – respectively.

In the last encounter with Martinaise’s communist reading group, after reading A Brief Look at Infra-Materialism, the detective attempts to rebuild the matchbox structure alongside his new comrades. A feat of “physics-defying architecture” in-game, the structure is based on a the Monument to the Third International designed by Soviet constructivist Vladimir Tatlin, which itself was never built. When, in the first encounter with the group, the structure immediately falls down; this time, with careful construction, it stands. For a second, the game’s viewport lingers, along with its characters gazes, in seeming awe of the impossibility of such a thing. The plasm’s – ideology’s – theoretic potential, realized just for one moment. Upon the matchbox monument’s subsequent collapse, the leader of the group says, in a somewhat more hushed tone: “This was exactly what we tried to achieve, nothing more and nothing less.”

One tin revolutionary soldier

Just before meeting the Insulindian Phasmid, the detective solves the case which has driven the story. A deserter from the revolutionary guard of Revachol named Iosef Lilianovich Dros who, as a teenager, had worked as a political commissar during the war long before the game begins, now an old man, had been hiding out in an otherwise abandoned communist military installation on a small island in the bay which abuts the port. During what was called Operation Death Blow by the Coalition of Nation aggressors he had deserted his post, fearing for his life. After surviving the massacre, he returned to find all of his comrades dead by shelling or drowning. The trauma of this event pressed him to take on a personal, endless war against the ideological and repressive forces of capital. While initially he joined with other leftover revolutionaries, after rounds of mass executions, only he remained both alive and unintegrated into society. While he had given up on revolution, he used his rifle and training to watch Martinaise and snipe down people who he personally did not like.

Despite being an ideological officer, with a robust Mazovian political education, Dros ends up operating as an avatar of individualism – as one, lonely actor carrying out tasks for no goal beyond personal fulfillment. Half-justifying these actions to himself through political means, he knows that they are nothing more than petty grievances, even if they resulted in the death of others. It is revealed, in speaking to Dros, that the union boss had at one point met the man and offered him social housing, and that he had declined the offer despite believing in the good of the program. Instead he stays in the bay at the abandoned base, unknowingly taking in small doses of neurotoxin from the Insulindian Phasmid. The Deserter, in his determination to remain apart from unjust society out of spite and ideology, ultimately consigns himself to the madness which capitalist forces, both militarily and psychologically, introduced.

Where the labor union and the reading group represent organizational failings in their own ways, The Deserter is undoubtedly the most tragic of Disco Elysium’s anti-capitalist political resistants. Traumatized by the violence of a colonial war of capital in his youth; then by the purging of resistance movements; and finally by the despair of being, even willfully, isolated from society – Dros turns to stochastic violence. Killing random people he has no personal attachment to, but rather feels fail to meet a social litmus.

In his early work, Marx wrote on the way in which, then early, capitalist society sequesters people away from each other through alienation:

“In estranging from man (1) nature, and (2) himself, his own active functions, his life-activity, estranged labour estranges the species from man. It turns for him the life of the species into a means of individual life. First it estranges the life of the species and individual life, and secondly it makes individual life in its abstract form the purpose of the life of the species, likewise in its abstract and estranged form.” (Marx 1978, 75)

He would go on to develop these ideas into a more robust critique of capitalism, and describe with more detail and precision the struggle of workers within society. I find this early description of “estrangement” maybe most relevant here though. In Disco Elysium, The Deserter and other Martinaise characters, to a lesser degree, are estranged from both the species of humanity as a natural collection of people, and from themselves and their everyday humanities. They operate as individuals, yes, but specifically as individuals estranged from themselves and their past/future potentialities, estranged from the humanity of society. They are not just the products of the individuation of social problems, they are the individuation of social problems.

The estrangement of Dros, and his spiteful, personal actions are just another way that Disco Elysium represents the futility of an anti-capitalist existence under the militarized, global regime-system. Driven over the edge of sanity by his own inability to change the world, and psychologically altered by the neurotoxins of the Phasmid – a physical manifestation of the always-already (Althusser 1970) new and unknown – Dros’ is a cautionary tale, if ever there was one. Taking action, facing systemic violence alone, is a futile and self-destructive impulse, the only ends of which are resentment of, and estrangement from, the world and humanity.

Organizing your self

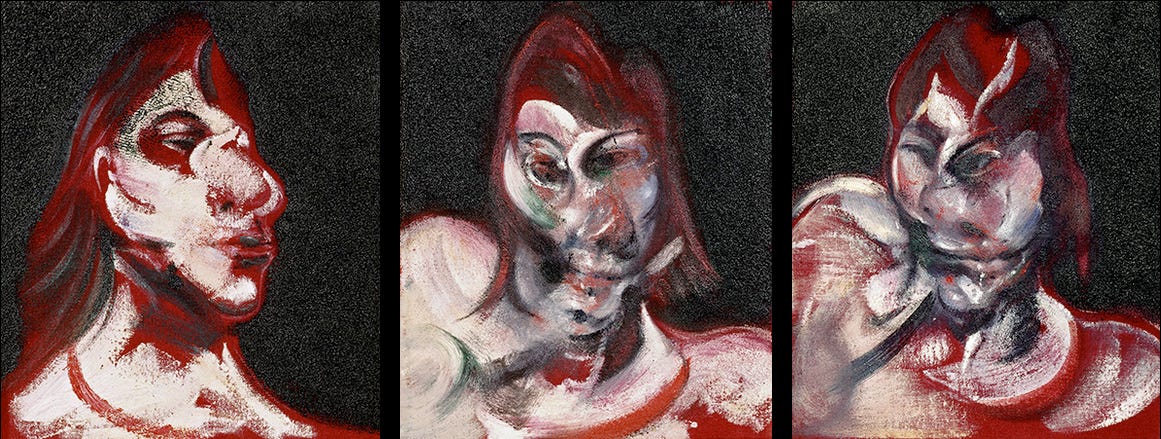

Where Disco Elysium is a game which foregrounds critiques of society throughout its text, its story is told and explored through a self-reflective mode. Within the mind of the detective, are more than 24 internal characters who provide insight in interactions with the world. Represented by oil-painting portraits reminiscent of Francis Bacon’s surrealist style, especially in works like his Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes triptych and similar post-1960 portraiture, these grotesque internal monologues act as angels and devils on the detective’s, crowded, shoulder. They present their contributions in a wide variety of forms, from heckling, to hubristic encouragement, to prose-poetic descriptions of the world – they even fight with one another directly, each with a distinct voice. While these skill-characters are the disorganized fragments of a broken man’s mind and body, they are too the constituent parts of all people in the world of Disco Elysium’s skill-checks – a role-playing game mechanic which matches your skill levels against those of obstacles and other people through modified dice rolls. In this way, the quest to ‘get yourself organized’ is more than just a call to a) organize with other people and b) organize one’s physical life, but also to c) organize oneself psychologically, to moderate the ugly presidium of neurochemical impulses which mediate our historical situation of being-in-the-world (Marcuse 2005, 3-4).

Where this call to self-organization is perhaps easily confusable with Dros’ lone-wolf tragedy, and is even perhaps most recognizable as having been claimed by the contemporary far-right (Burgis 2022), Disco Elysium makes clear that in a world – a society – which does not view the welfare and dignity of people as valuable, there is no real potential to organize one’s thoughts. The material conditions of the world do not privilege comfortable self-actualization for any but those wealthy enough to afford it. This implication is underscored throughout the internal dialogues, and options for ‘outrageous’ external dialogue and action, which persist throughout the game. In one instance, I accidentally directed the detective to shoot himself in a failed attempt to assert his authority via the idea that he is verifiably crazy. The game lead me to question, “would he really do it?” – only to be rudely redirected to the game’s start menu after being shown a news article on the detective’s death:

“DERANGED COP KILLS HIMSELF

Citizens in shock as a deranged law official, reportedly from the 41st precinct, shot himself in the head last night in the middle of a crowded cafeteria in downtown Martinaise. The exact details of the incident have not been revealed, but first-hand witnesses claim that the officer was making a point.” (Disco Elysium game over #7)

“Making a point” which jeopardizes, or perhaps truncates, one’s ability to continue on in the world, is in Disco Elysium “deranged.” It is unreasonable to kill one’s self, even in a world without reason.

Suicide is a regular topic throughout the communist-aligned elements of the game, a point of disinformation and ridicule. Within the history of Elysium, Kras Mazov was officially said to have killed himself; however, through researching a thought about his death the detective learns that he was either assassinated or died during a bombing of the communist headquarters during the war. Knowing that he did not give up, increases the detective’s morale whenever he loses a skill-check. The knowledge that others never gave up, fuels the will of those still fighting. Within the infra-materialist reading group, the frequent suicides of the Gottwaldian Mazovians is also the butt of jokes. The leader of the reading group critiques the Gottwaldians for being “depressed liberals” incapable of anything but critiquing capitalism from within it and writing “long works of criticism that make you want to commit suicide.” When the detective replies how “that sounds miserable,” the leader disrespectfully retorts “It is miserable. That’s probably why they’re always committing suicide.” Returning to Žižek on Lacan, the loss of jouissance that comes with touching knowledge need not be a demon core, but neither should pure ideology be allowed to obscure material reality – these together can begin the project of forging the present into the future.

This is the crux of Disco Elysium, its philosophical thesis statement. It is unethical, even in an irrational, inhumane, unchangeable situation, to give up working for the betterment all those who live in it. No matter the fact of the task’s futility, short of sudden apocalypse, the only real choice is to “build communism” – a better life for everyone – arm-in-arm, as best as is possible, and try not to lose sight of oneself and the turning of the world in the process.

Works Cited

Althusser, Louis. 1964. “Marxism and Humanism.” Cahiers de l’I.S.E.A., June.

———. 1970. “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses.” Translated by Ben Brewster. La Pensée. https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/althusser/1970/ideology.htm.

Bacon, Francis. Three Studies for Portrait of Henrietta Moraes. 1963. Oil on canvas, 14 x 12 in (3 panels). Museum of Modern Art, New York. https://www.francis-bacon.com/artworks/paintings/three-studies-portrait-henrietta-moraes.

Burgis, Ben. 2022. “Jordan Peterson’s Politics Make Life Harder for Young Men.” The Daily Beast, November 26, 2022, sec. politics. https://www.thedailybeast.com/jordan-petersons-politics-make-life-harder-for-young-men.

Engels, Friedrick. 1972. Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Translated by Edward Aveling. Little Marx LIbrary. New York: International Publishers.

Erdmann, J.E. 1896. Outlines of Logic and Metaphysics. Translated by B.C. Burt. New York.

Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero Books. Winchester, UK: Zero Books.

Gittlitz, A. M. 2020. I Want to Believe: Posadism, UFOs and Apocalypse Communism. London: Pluto Press.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich. 1961. What Is to Be Done? Translated by Joe Fineberg and George Hanna. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Lévy, Pierre. 1997. Collective Intelligence: Mankind’s Emerging World in Cyberspace. New York: Plenum Trade.

Marcuse, Herbert. 2005. Heideggerian Marxism. Edited by Richard Wolin and John Abromeit. European Horizons. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Marx, Karl. 1978. “Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844.” In The Marx-Engels Reader, edited by Robert C. Tucker, 2d ed, 66–124. New York: Norton.

Williams, Raymond. 1977. “Structures of Feeling.” In Marxism and Literature, First, 128–35. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2008. The Sublime Object of Ideology. Second edition. The Essential Žižek. London: Verso.

———. 2020. A Left That Dares to Speak Its Name: Untimely Interventions. Cambridge, UK ; Medford, MA: Polity.

Ludography

EggNut. Backbone. Raw Fury. PC. 2021.

ZA/UM. Disco Elysium. ZA/UM. PC. 2019.

I’m hopefully going to write up my 2022 AOTY list sometime soon, so look out for that. Like I said, and you’ve now read, it’s a been busy while. Here’s your music reccomendation until I get around to writing something here again.